Private equity investor and underwater explorer Victor Vescovo will soon sell his submarine, which he calls the Limiting Factor. And the U.S. government, with private sector partners, should send someone to kick the tires.

Of course the U.S. government already has plenty of submarines, but this is no ordinary submarine. Some would say it is not a submarine at all, but a submersible, the difference being that a submarine is meant to travel long horizontal distances underwater at depths down to 600 feet or so while a submersible is meant primarily to travel up and down to great depths.

What makes Vescovo’s vessel truly extraordinary is that it is the world’s only operational submersible that that can reach the ocean’s ultimate bottom, the seabed of the Challenger Deep in the Marianas Trench, almost 36,000 feet beneath the waves. For perspective, if Mount Everest were magically relocated to the Challenger Deep, its summit would lay more then 6,000 feet—over a mile—below the surface.

Many readers will remember the first dive to the bottom of the Challenger Deep, in 1960, by the bathyscaphe Trieste. Immediately after that dive, a government press release told the world “the United States now possesses the capability for manned exploration of the sea down to the deepest part of its floor.” But almost before the ink had dried on this claim, the U.S. Navy reclassified Trieste, limiting it to depths shallower than 20,000 feet. Now decommissioned, it hangs in the Naval Museum in Washington, D.C.

In the ensuing decades, other extraordinary submersibles were launched, not only by the United States but also by Russia, Japan, China, France, and others. However, none were capable of diving deeper than about 20,000 feet. This was justifiable, said proponents, because more than 99 percent of the world’s oceans are shallower than 20,000 feet. Both the costs and risks of going deeper, the reasoning went, were not warranted by the sliver of oceans that would remain off limits. But this reasoning overlooks one important reality: that tiny sliver covers an area considerably larger than that of, say, Texas. This is, some might say, a rather large chunk of real estate to ignore.

The second dive to the bottom of the Challenger Deep did not come until 2012, when movie mogul James Cameron made the trip down and back, supported by Rolex, the National Geographic Society, and others. His submersible, like the Trieste before it, made a single dive. Afterwards, and entirely unrelated to the dive itself, it was damaged by fire. It now sits in storage, its current condition unknown to the public.

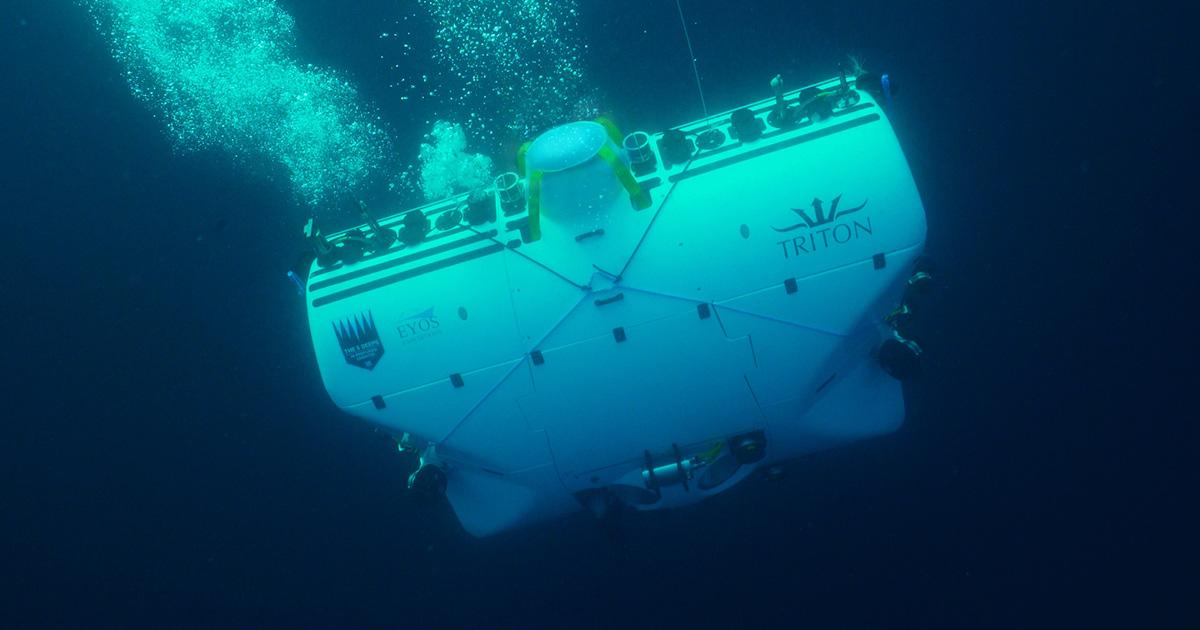

Enter Vescovo and his Five Deeps Expedition in 2018, when an announcement proclaimed that the Limiting Factor, built in secret by Triton Submersibles of Florida, would dive to the bottom of five deep ocean trenches, all but one of them deeper than 20,000 feet. The announcement, at first blush, hardly seemed credible. It reeked of hubris. It seemed more than possible that the expedition would fail, and at least one mode of failure could involve loss of both the Limiting Factor and her crew.

So far, with only the Arctic Ocean trench left on their agenda, the expedition has exceeded expectations. Between April 28 and May 5, 2019, the Limiting Factor went to the bottom of the Challenger Deep and (importantly) back to the surface four times.

Why, one might wonder, would anyone put humans at risk in the depths when robots arguably have capabilities comparable to those of submersibles? While no existing underwater robot can dive the Challenger Deep, two robots—both since lost at sea—have been there and back. In addition, so called “landers,” essentially disposable instrument and sampling packages, have been to the bottom and sent back data and samples. But no robot will ever capture the human interest that a manned program captures. In an expression that I first heard from Trieste pilot Don Walsh during an interview in his home office in 2017, and which he himself attributes to James Cameron, “No kid ever wanted to grow up to be a robot.” Robots, to be sure, should be part of future exploration of the world’s greatest depths, but people are needed too.

We are a nation of explorers, a culture happy to embrace measured risks. We see value in being the first and the best when it comes to understanding and experiencing unknowns so profound that we cannot responsibly speculate on what they might be. But why specifically should the US government be interested in acquiring the Limiting Factor? Partly because this is an opportunity to buy a system with proven capabilities for far less money than it could be built by the public sector. Partly to make good on the 1960 claim of deep-sea capabilities and to reclaim absolute leadership in this deepest of realms. And partly because this is a chance to remind ourselves of our rich maritime heritage and to underscore our strength in an arena that, for the time being, remains unmilitarized.

And how, exactly, should a government that persistently reaches for new records in deficit spending pursue the purchase, maintenance, and operation of a vessel as unique as the Limiting Factor? Outright ownership through the U.S. Navy or the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration is possible, but a better solution, one more suited to our times, would involve a public-private partnership. America has more billionaires than any other nation on the planet. What is to stop one or more of these tycoons, many of whom already own lesser submersibles , from stepping up to support what will be an exciting new chapter of manned exploration? What is to stop a union of the best characteristics of the private sector with the best characteristics of the public sector? Perhaps nothing more than the vision to do so.

Op ed by Bill Streever

Bill Streever is a long-term diver, biologist, and writer. His most recent book was In Oceans Deep: Courage, Innovation and Adventure Beneath the Waves.