Until 2019 only three people had been Challenger Deep, which at nearly 11km deep, is the deepest point of the ocean. Recently, Nicole Yamase became the first Pacific Islander to journey to the bottom of the sea. Nicole Yamase is currently a student at the University of Hawaii at Manoa, but she’s a citizen of the Federated States of Micronesia (FSM). “I was born in Pohnpei [Micronesia]” she said. “My dad works for the government, so we moved around a lot. A few years later, my family moved to Palau where we lived for about four years. Then we moved to Saipan for about five years, moved back to Pohnpei for like a year, but then my dad got transferred to Chuuk. That’s where I stayed for seven years and attended Xavier High School. Then, right after high school, I came up to Hawaii to further my education at Chaminade University [of Honolulu]”. Thanks to her island hopping early years, Nicole says she’s “a child of the islands.”

While she was in high school, Nicole became interested in climate change and realized that she wanted to study conservation and the environment. But there are few opportunities to study environmental science in the FSM. Luckily, Nicole was also able to participate in one of several projects funded by the US National Science Foundation (NSF) to promote science in the region, after enrolling in her first year of university, and it helped her to decide her career path. “My project was on the relative abundance of fish that were collected for the ornamental fish trade. So, I did a lot of snorkeling around the island.” Nicole’s research was conducted under Dr. Gail Grabowsky, and involved conducting surveys on reefs, looking at the number and sizes of fish, especially the yellow tang, a popular fish for the aquarium trade. She found that fish numbers were low, and also that there were few juveniles, as these tended to be targeted by collectors for the aquarium trade. In some locations, such as Waikiki, the fish on the reefs were heavily affected. At the end of the summer she gave a presentation on her results.

While she was in high school, Nicole became interested in climate change and realized that she wanted to study conservation and the environment. But there are few opportunities to study environmental science in the FSM. Luckily, Nicole was also able to participate in one of several projects funded by the US National Science Foundation (NSF) to promote science in the region, after enrolling in her first year of university, and it helped her to decide her career path. “My project was on the relative abundance of fish that were collected for the ornamental fish trade. So, I did a lot of snorkeling around the island.” Nicole’s research was conducted under Dr. Gail Grabowsky, and involved conducting surveys on reefs, looking at the number and sizes of fish, especially the yellow tang, a popular fish for the aquarium trade. She found that fish numbers were low, and also that there were few juveniles, as these tended to be targeted by collectors for the aquarium trade. In some locations, such as Waikiki, the fish on the reefs were heavily affected. At the end of the summer she gave a presentation on her results.

Having conducted marine research during her internship, and having “got a taste of the ocean,” she then wanted to learn more about the terrestrial side of environmental and conservation research, to see which path she wanted to take. So the following summer she took part in the NSF-funded Native American and Pacific Islander research experience in Costa Rica, where she studied frogs at the Las Cruces Biological Station.

Having conducted marine research during her internship, and having “got a taste of the ocean,” she then wanted to learn more about the terrestrial side of environmental and conservation research, to see which path she wanted to take. So the following summer she took part in the NSF-funded Native American and Pacific Islander research experience in Costa Rica, where she studied frogs at the Las Cruces Biological Station.

She found that Costa Rica reminded her of her childhood on Pohnpei. “It was like home, being in the forest. And it was so funny because the students from the mainland [US] were just sweating bullets. Their shirts were always so wet, but the Pacific Islanders were just loving it. So cool and dry. And we would ask them like, are you guys okay? You need water or something? So it was really fun.”

Nicole snorkeling and taking pics of algae on a reef in Chuuk, Federated States of Micronesia; Photo credit: Lisa Marie Billy

Nicole snorkeling and taking pics of algae on a reef in Chuuk, Federated States of Micronesia; Photo credit: Lisa Marie Billy

For her studies in Costa Rica she looked at the territorial behavior of tiny, tink frogs (so called because of their “tink tink” calls). “They’re territorial and have calling sites. They also come out at night, so that’s when I did my field work. I had to fully gear up with my snake boots, my headlamp, and I would just stand there in the dark. I had to leave my light off because it would scare them, so I would stand there in the dark with my notebook, and just wait for them to make noise. Then I would have to look for them in the bromeliads, and tie tape to the flowers so that I knew that was their calling territory. And then I looked at how many frogs would be around them to see how big their territory was based on their “tink-ing.”

After that summer of studying frogs in the cloud forests of Costa Rica, she decided that she should try to narrow her interests and specialize: “Both experiences were amazing, but really, I was leaning towards the ocean more.”

Yamase Costa Rica – Doing fieldwork at night (finding tink frogs!) in the Wilson Botanical Garden at the Las Cruces Biological Station (NSF funded 2011 Native American and Pacific Islander Research Experience in Costa Rica). Credit: Nicole Yamase

Yamase Costa Rica – Doing fieldwork at night (finding tink frogs!) in the Wilson Botanical Garden at the Las Cruces Biological Station (NSF funded 2011 Native American and Pacific Islander Research Experience in Costa Rica). Credit: Nicole Yamase

The programs in which she participated encouraged her to apply for conferences, and she was given support to attend the SACNAS conference (Society for the Advancement of Chicanos/Hispanics and Native Americans in Science), with her travel and lodging covered by grants – “our whole trip was free!” she exclaimed gleefully.

“It was from the experience of going to these conferences,” added Nicole, “that I realized there’s not many Pacific Islanders in science because when we saw each other, it was so rare. We’re like, ‘Oh my gosh, you’re from the Islands too!’ And you know, we’d all get together and just stay together because it was such a sight to see another person, another Pacific Islander there. Because of these internships, I’ve really been an advocate for STEM education for Pacific Islanders, and participation in these summer internships. Because being in these NSF internships, with other Pacific Islanders who share the same passion, it’s such … fuel for us. Like we need to multiply. We need more of us. It’s such a huge motivation to be surrounded by Pacific Islanders, with the same passion. It’s what has kept me going. I was listening to a lecture today about the importance of being in peer groups. If you’re always the odd one out, it’s much harder than if you’re in a community.”

She also explained that, growing up in her culture, young people are expected to sit back and listen to their elders, and not take on leadership roles. “You knew who the Pacific Islanders were in the classroom,” she said. “We’d all be in the back of the classroom. You know, none of us would raise our head or answer questions – but we would whisper the answer to each other. We wouldn’t say it out loud.” She said that her experience helped her and her fellow Pacific Islanders, giving them confidence to speak out, participate and engage. “These summer internships really made us step up – presenting in front of a lot of people, talking to doctorates, talking to older scientists,” she said. “These NSF internships really, really played a huge part in my becoming a spokesperson and a promoter for these opportunities that are out here for us.”

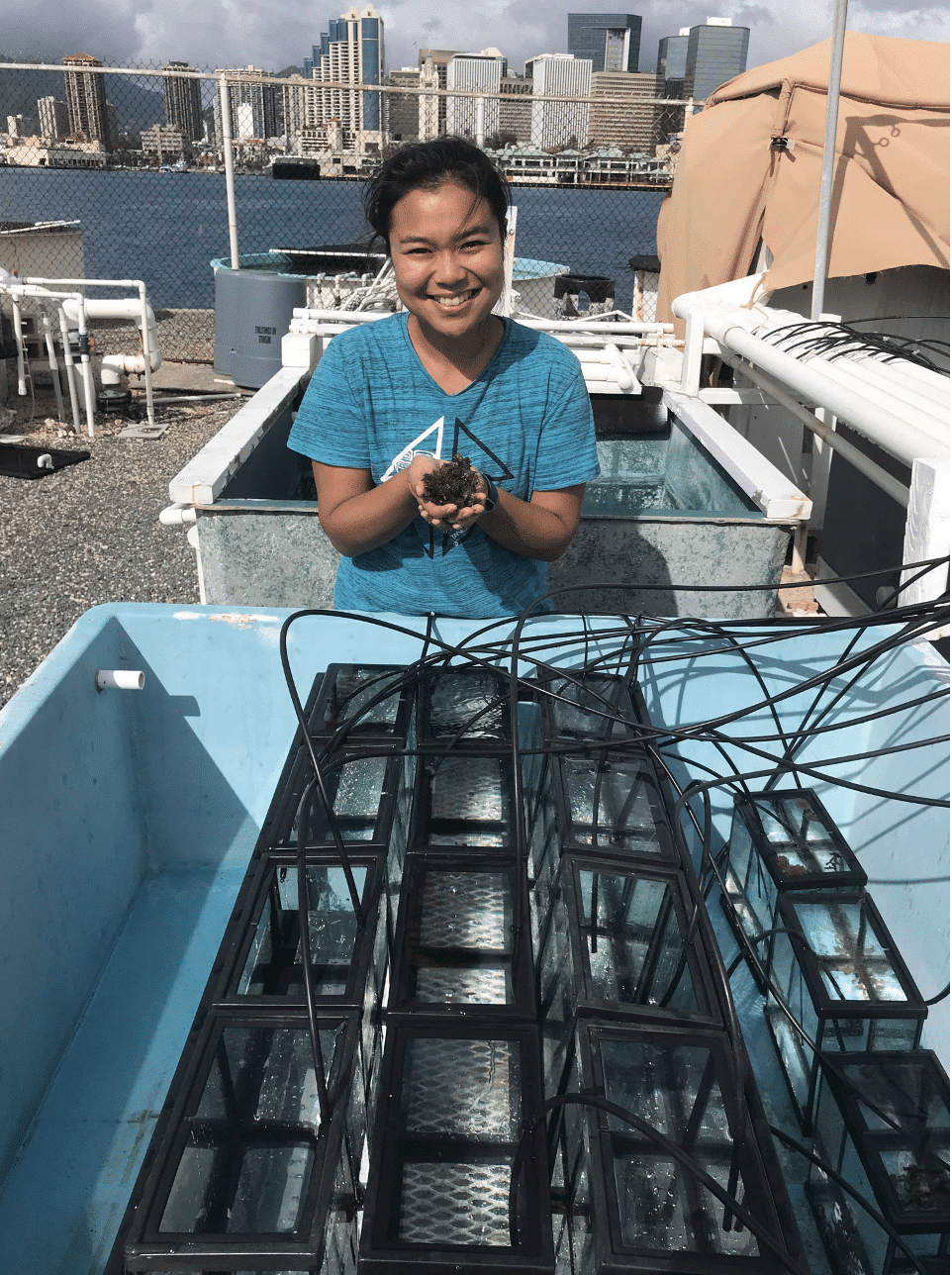

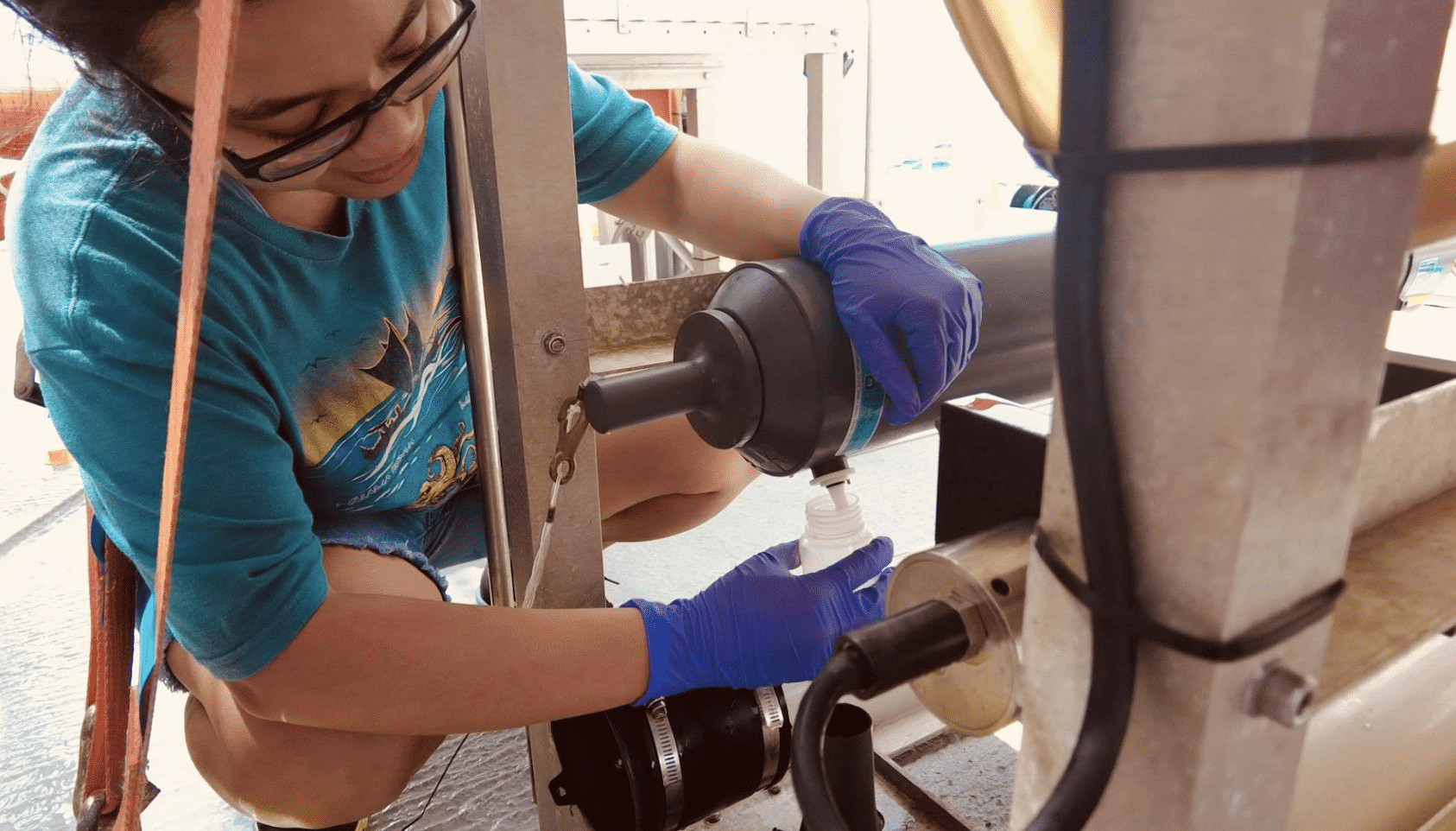

Nicole is currently doing her PhD research on a little-studied species of algae that is found in the Northwest Hawaiian Islands, funded by several scholarships, with her tuition paid for by the Bill Raynor Micronesia Challenge Scholarship from the Micronesia Conservation Trust. It was through this scholarship that she ended up diving to the very bottom of the ocean.

Adventurer and submersible pilot Victor Vescovo had organized several recent submersible expeditions to the Mariana Trench. However, he thought it was important that, as the trench and Challenger Deep are located in the Federated States of Micronesia (FSM) waters, a citizen of the FSM should have the opportunity to visit this famous ocean location. The Micronesian Conservation Trust put forward Nicole as a possible candidate.

Nicole said that unfortunately there was not a lot of competition; this was unfortunate because when she gets her PhD at the end of the year she will be the first FSM citizen to have ever earned a doctorate in marine biology. Despite the abundant marine biodiversity in Micronesian waters and the region’s long cultural connection with the oceans, very few students in the FSM study science, let alone marine science.

“You know, just thinking of this field, the thought of the science classes, the math classes, the physics classes, that’s what is holding students back from being in this field, just the fear of not being able to pass the class. Well, I’m not the brightest person. If I can do it, honestly, anybody can. It’s because I had a great support system, all my advisors, my mentors from these summer internships.”

Nicole added sadly, “When I go home and talk to students at the college of Micronesia and share my work, there’s so many of them that are passionate about the marine biology field, but then they come talk to me and say, Oh, I’m going to switch my major because I won’t be able to pass the science classes. And I say to them, how do you even know? You haven’t even taken the science classes. You know, it’s that mentality that I’m really trying to break. It’s sad because, I’ve made it, and they can too. I didn’t have great grades, or GRE score, but I had strong recommendation letters. I was passionate, and I had these experiences. My mentors and advisors saw that – they didn’t just look at the grades. They looked at me as a complete package.”

Nicole hopes that she will serve as a role model to encourage other Pacific Islanders to find the confidence to study marine sciences.

Victor Vescovo also saw the potential that Nicole had, and asked her to be a representative for Micronesia on his latest expedition with the DSSV Pressure Drop to the Challenger Deep

She said that the crew on the ship was very welcoming. “Everybody was so very helpful, very professional, but they knew how to have fun. Before I left, I was really scared that everybody’s going to ask what are you studying? What’s your background? What’s this, what’s that? No, everybody was so nice and very down to earth. And that’s what made the trip really easy for me, to process everything, because there wasn’t any pressure from the crew to know everything, because I didn’t have time to know everything.”

On the day of the dive, she went to the ship’s kitchen to get a packed lunch. They had an Austrian chef, Warren, who made her a traditional Austrian apple strudel. It’s now a tradition if you’re going to Challenger Deep, you take strudel with you for lunch. They also gave her a sandwich, some granola bars and a tiny bottle of water.

“You don’t drink any water.” Nicole said, “We had to dehydrate the night before and also the morning of the dive. So that’s all we had, a tiny bottle of water. Because, famously, there is no bathroom on the submersible.” She also added, as soon as they surfaced, and she got back to the ship, the first thing she did was go straight to the bathroom. That’s a real limiting factor on submersibles. If they could just have a bathroom, they could do so much more science.

When they were waiting to submerge in the deep sea submersible Limiting Factor, floating at the surface, was the worst part of the dive. Nicole said that you needed a strong stomach “because we were just bobbing on the surface, for maybe five or 10 minutes. And it gets hot in the sub pretty quickly, so I was sweating. I was feeling nauseous, but then once we unhooked and started going down, it went away. It was just smooth sailing all the way down for four hours. We had three small windows. Two at the top and one right next to our feet. And so I was just watching the colors of the blue change from light to dark, which was pretty cool.”

To pass the time on the way down, they talked about each other’s work, and Victor explained about the equipment on the submarine, explaining what all of the buttons did.

They also listened to music. Victor asked Nicole what sort of music she liked – she explained that she was a fan of classics, like Chicago and Abba. So, he flicked a switch and “Dancing Queen” echoed around the submersible. “In the movie of my life, that is going to be THE scene, dancing in the submersible to ‘Dancing Queen.’ He also played us Smoky Mountain rain and even a Britney Spears song.” Every 15 minutes, Victor had to report to the surface that all was well and life support was functioning, so he’d pause, give his report, and then they’d go back to Abba.

Finally, the submersible reached the deepest part of the world, 10,911m underwater. “It looked like a desert with scattered rocks. That’s the best I can explain it. A desert or another planet. It really did feel like I was also on another planet – I felt like I was in Star Wars. We had to search for our deep sea lander – which I thought looked like R2D2 and, well, I suppose Victor has a sort of Obi-Wan Kenobi sort of look to him. So it was like Star Wars, but under the ocean.”

However, despite being one of the deepest, remotest parts of the world, which until that point had only been visited by a dozen people, there were sad signs of human disturbance.

There were lots of cables there, scattered around on the ocean floor. Tethers lines just lying on the ocean bottom. It was dangerous, and Victor told me to look out for them because they could have gotten stuck in the propellers.” This debris could have been brought in by currents from other locations, but there are concerns that previous research projects in this deep sea region may have discarded these cables, leaving them on the ocean bottom. Although the Mariana Trench is within the Mariana Trench Marine National Monument and should be protected, its remote location makes managing activities difficult. “There needs to be some sort of agreement or treaty, about research and these trench areas” said Nicole. An international agreement similar to one that governs international research and protects the fragile environment and species in Antarctica might help to better protect this unique and remote location.

The remoteness of the location should not be underestimated – until 2019 only 3 people had visited Challenger Deep: in 1960 Jacques Picard and Don Walsh were the first to explore the location in the submersible Trieste and then James Cameron in the Deepsea Challenger submersible in 2012 . In comparison, 12 people have been to the moon. Since Victor Vescovo started visiting in the submersible DSV Limiting Factor in 2019, however, a further 19 people have visited Challenger Deep, including Vescovo, three Chinese scientists in the Chinese deep-sea submersible Fendouzhe, and Nicole. Nicole was only the 20th person to have visited Challenger Deep, the fourth female visitor (former Astronaut and NOAA scientist Dr. Katheryn Sullivan, Vanessa O’Brien, the first woman to climb Mount Everest, and one member of the Chinese expeditions preceded her). However, she is the second youngest (Don Walsh was a few months younger than she when he dove in the trench) and the first Pacific Islander.

“However, being a representative for the Pacific Islander, the coastal waters of which also encompass one of the largest parts of the world’s oceans, was daunting for her. In fact, she said that was more intimidating than the voyage to the bottom of the trench. “The biggest weight I had on me was how to represent. All of us. How do I represent Pacific Islanders?” she said.

“I talked to someone I know, who is a native Hawaiian navigator, and a student of famous Polynesian master navigator Pius Mau Piailug (or Papa Mau), and he said bring Papa Mau; you will bring all of us with you. And so that’s why I brought a canoe with me as a representation of all of us, of all Pacific Islanders, because that is something we can all relate to, you know?”

When Nicole arrived in Guam, on the first part of her journey to the Trench, she went up onto the ship’s deck: “I was just taking it all in and I saw a boat called Papa Mau, so it was like a spiritual message. Papa Mau, he’s here. Then I looked to my other side and there’s a small boat named Micronesia. So I’m like, oh my gosh, what are the [chances] of both boats coming into that port in Guam on the same morning, my first morning in Guam. So I was, wow, what a sign! That same morning, we left the dock to the Mariana Trench, and Papa Mau also left with us. So I was like, oh my gosh, it’s like he was there. They were all here with me as we were heading out. It’s so crazy. I cried. So that experience really made me feel so calm. I felt so grounded. Usually, I’m a really excited and loud person. But, that morning I was just chill. It was almost spiritual, I felt like I was going home. I’m going to go visit a relative, but just underwater. I felt so at peace. It was crazy because I’m usually jumping and screaming when something exciting happens, you know? But in the submarine I was just so calm. I didn’t think of anything. I was not scared whatsoever.”

By E.C.M. Parsons