California coastal waters contain some of our nation’s more economically valuable fisheries, including salmon, crabs and shellfish. Yet, these fisheries are also some of the most vulnerable to the potential harmful effects of ocean acidification on marine life. That increase in acidity is caused by the ocean absorbing excess carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

100 years and 2,000 shells later

100 years and 2,000 shells later

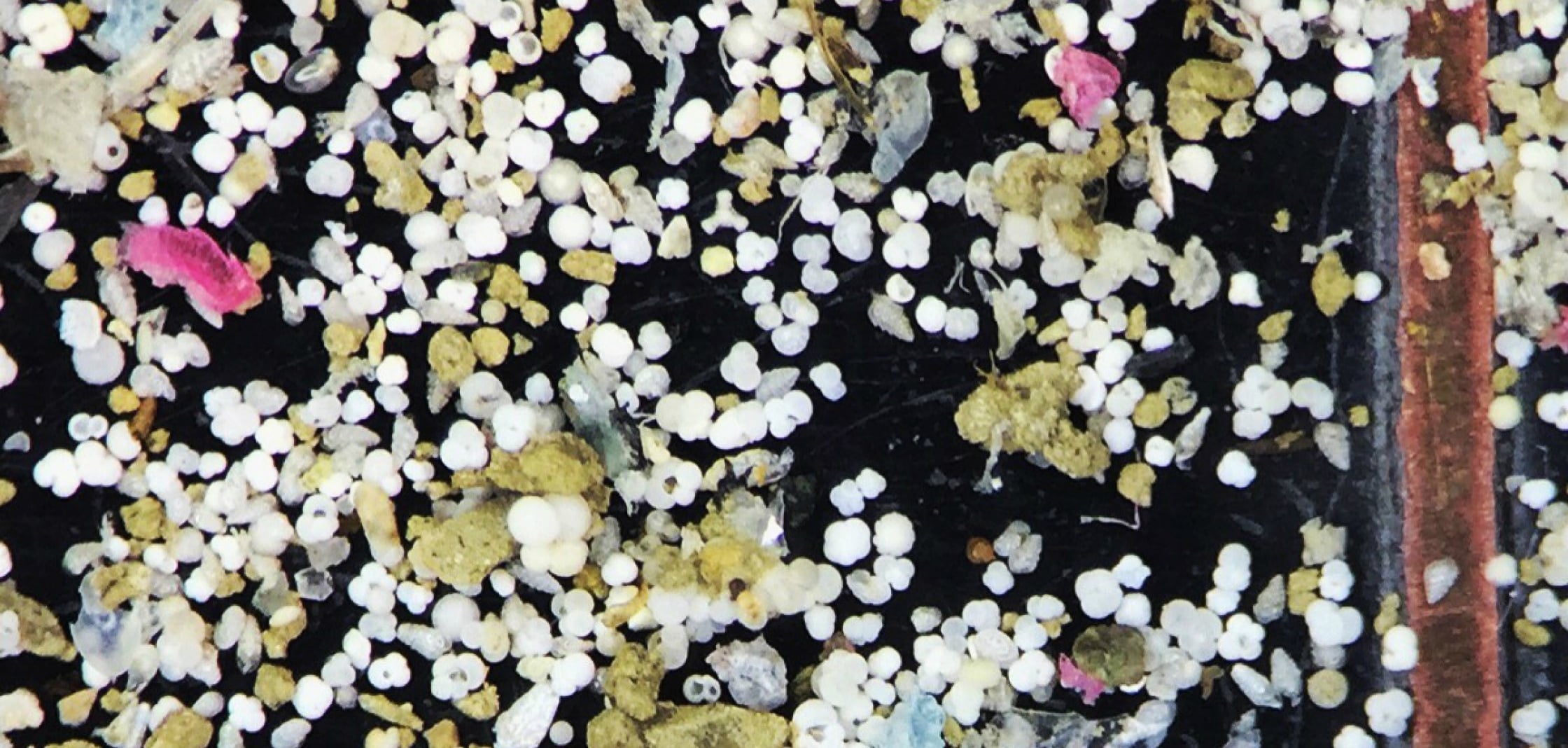

In the new study published in the journal Nature Geoscience, scientists examined nearly 2,000 shells of microscopic animals called foraminifera by taking core samples from the seafloor off Santa Barbara and measuring how the shells of these animals have changed over a century.

Every day, the shells of dead foraminifera rain down on the ocean floor and are eventually covered by sediment. Layers of sediment containing shells form a vertical record of change. The scientists looked back through time, layer by layer, and measured changes in thickness of the shells.

“By measuring the thickness of the shells, we can provide a very accurate estimate of the ocean’s acidity level when the foraminifera were alive,” said lead author Emily Osborne, who used this novel technique to produce the longest record yet created of ocean acidification using directly measured marine species. She measured shells within cores that represented deposits dating back to 1895.

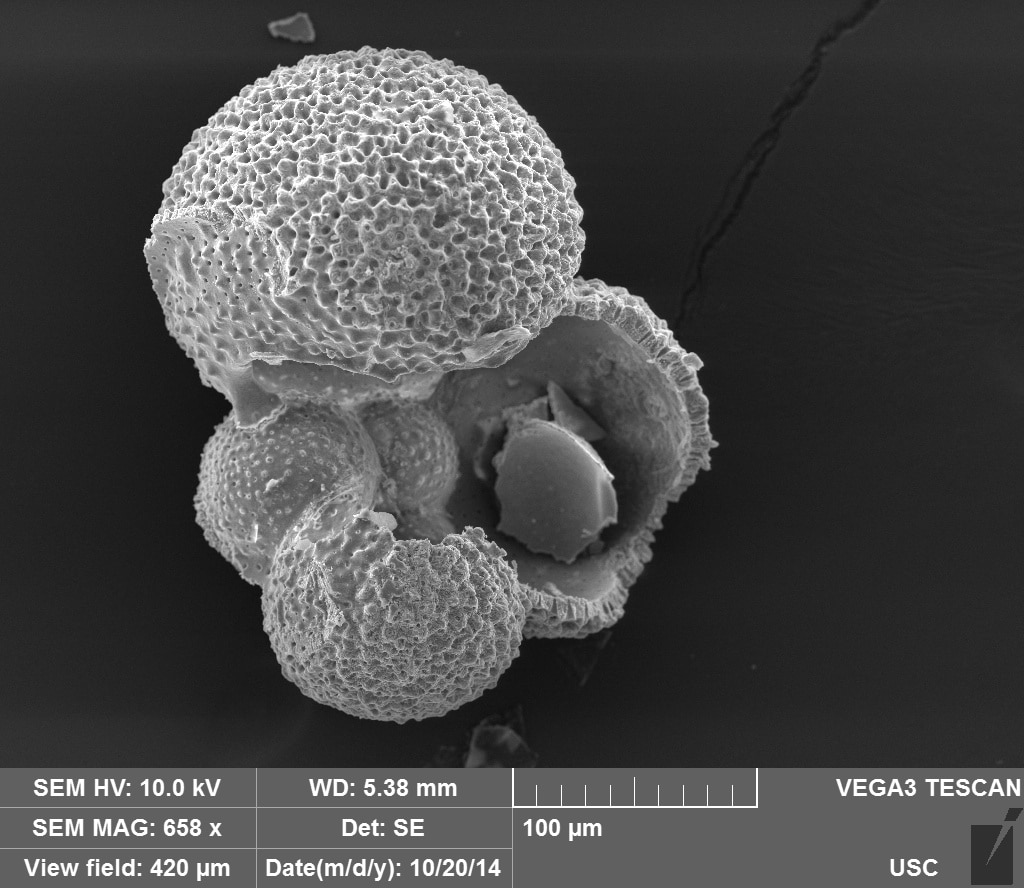

An image of the shell of a foraminifera — a microscopic marine animal — magnified and photographed 650 times its size by a scanning electron microscope. (Emily Osborne/NOAA)

An image of the shell of a foraminifera — a microscopic marine animal — magnified and photographed 650 times its size by a scanning electron microscope. (Emily Osborne/NOAA)

The fossil record also revealed an unexpected cyclical pattern: Though the waters increased their overall acidity over time, the shells revealed decade-long changes in the rise and fall of acidity. This pattern matched the Pacific Decadal Oscillation, a natural warming and cooling cycle. Human-caused carbon dioxide emissions are driving ocean acidification, but this natural variation also plays an important role in alleviating or amplifying ocean acidification.

“During the cool phases of the Pacific Decadal Oscillation, strengthened winds across the ocean drive carbon dioxide-rich waters upward toward the surface along the West Coast of the U.S.,” said Osborne, a scientist with NOAA’s Ocean Acidification Program. “It’s like a double whammy, increasing ocean acidification in this region of the world.”

Scientists hope to build on the new research to learn more about how changes in ocean acidification may be affecting other aspects of the marine ecosystem.

Story by NOAA

Journal Reference:

Emily B. Osborne, Robert C. Thunell, Nicolas Gruber, Richard A. Feely, Claudia R. Benitez-Nelson. Decadal variability in twentieth-century ocean acidification in the California Current Ecosystem. Nature Geoscience, 2019; DOI: 10.1038/s41561-019-0499-z