“The culturing of shellfish is by no means a way of nature conservation, but at least it keeps the mudflats in China and the bird food in a better condition than without this aquaculture,” Peng says.

Long Term Monitoring

Peng was the first to design a systematic survey of large parts of the intertidal mudflats along the 18,000 km of the Chinese coast. Between 2015 and 2023, he and his colleagues sampled 2,000 points on 40 different locations on a yearly basis, analyzing soil properties as well as living organisms that were found in the mud. The sampling was designed after the SIBES-program, that has been running as of 2008 on a grid with 5,000 locations in the Dutch Wadden Sea. “The work of Peng was one of the first that exported our SIBES-design to international waters,” the scientific coordinator of this monitoring program, NIOZ biologist Allert Bijleveld says. “We are thrilled to see this long-term program copied to other important nature areas around the world.”

Shellfish Culture

“My main finding was that the majority of the ‘bird food’ that we found in the mud was linked to the culturing of shellfish,” Peng says. “Overall, the number of waders like the great and the red knot are in decline along the Chinese coast, but at least on the locations where shellfish like Potamocorbula laevis were cultured in an extensive way, red knots as well as curlew sandpipers were doing relatively well. You can, therefore, say this aquaculture is a blessing in disguise for the migratory birds that depend on these ecosystems.”

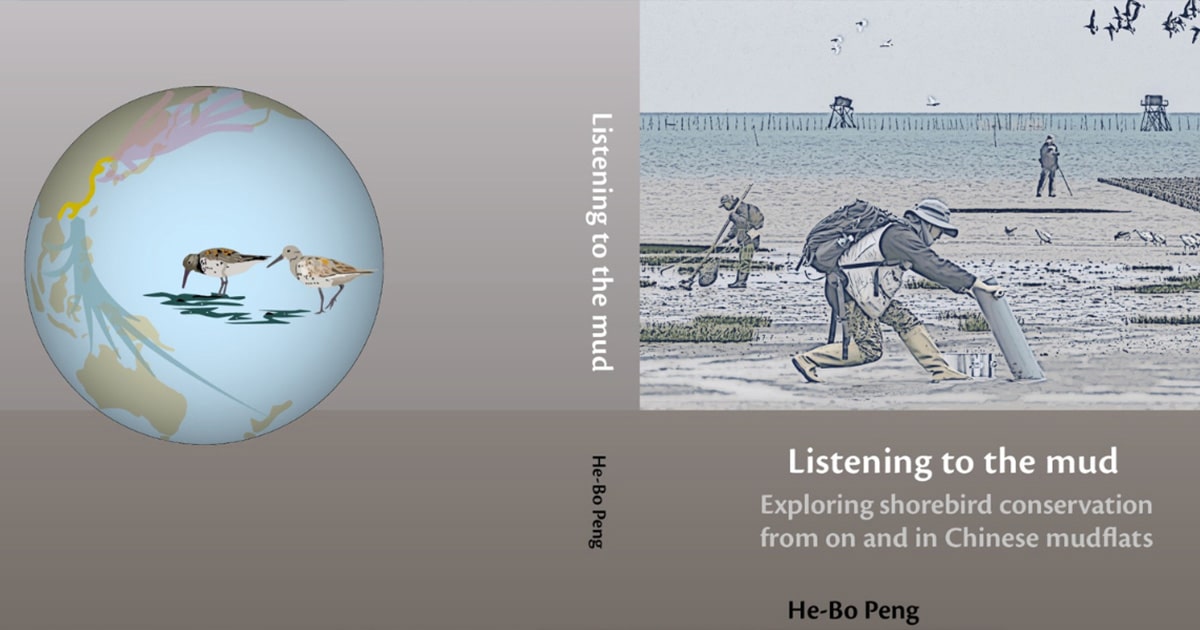

Hebo Peng is observing the birds. (Image credit: Hanming Tu)

Hebo Peng is observing the birds. (Image credit: Hanming Tu)

Reclaiming Land

The coast of the Yellow Sea has a long history of land reclamation for housing and industry. This reclaiming of land has stopped on most locations and there is even a modest increase in surface of mud flats on some parts. Peng: “On the locations where aquaculture has stopped as well, we see an almost unlimited exploitation of the mud flats by the local community. Therefore, the controlled management in aquaculture is a relatively good way to preserve at least some of the natural qualities of the intertidal flats.”

Listen to the Mud

In his dissertation, Peng advices to ‘listen to the mud.’ “This work is just a modest start of our understanding of these very important staging areas for birds on migration between eastern Siberia and Oceania. Through continuation of the long-term monitoring of the mud flats, as well as through tracking of birds with high tech transmitters, we can learn so much more in our quest for understanding of these ecosystems,” Peng says.

Hebo Peng and his colleague are sampling on the intertidal mudflats in Fangchenggang, China. (Image credit: Hanming Tu)

Hebo Peng and his colleague are sampling on the intertidal mudflats in Fangchenggang, China. (Image credit: Hanming Tu)

Daunting Task

Professor in global flyway ecology Theunis Piersma stresses the importance of the work of his Ph.D.-candidate. “Peng has shown that along the entire 18.000 km of the coastline, from the temperate climate in the north to the tropical parts in the south, biodiversity has homogenized under the influence of aquaculture. Given the intense use by local communities, returning these mudflats to true natural ecosystems will be a daunting task. But the incredible amount of work that Peng has done—and hopefully will continue to do—to monitor these ecosystems, will at least help us guide that process, should China choose to protect both the international travelling birds as well as the benthic biodiversity.”