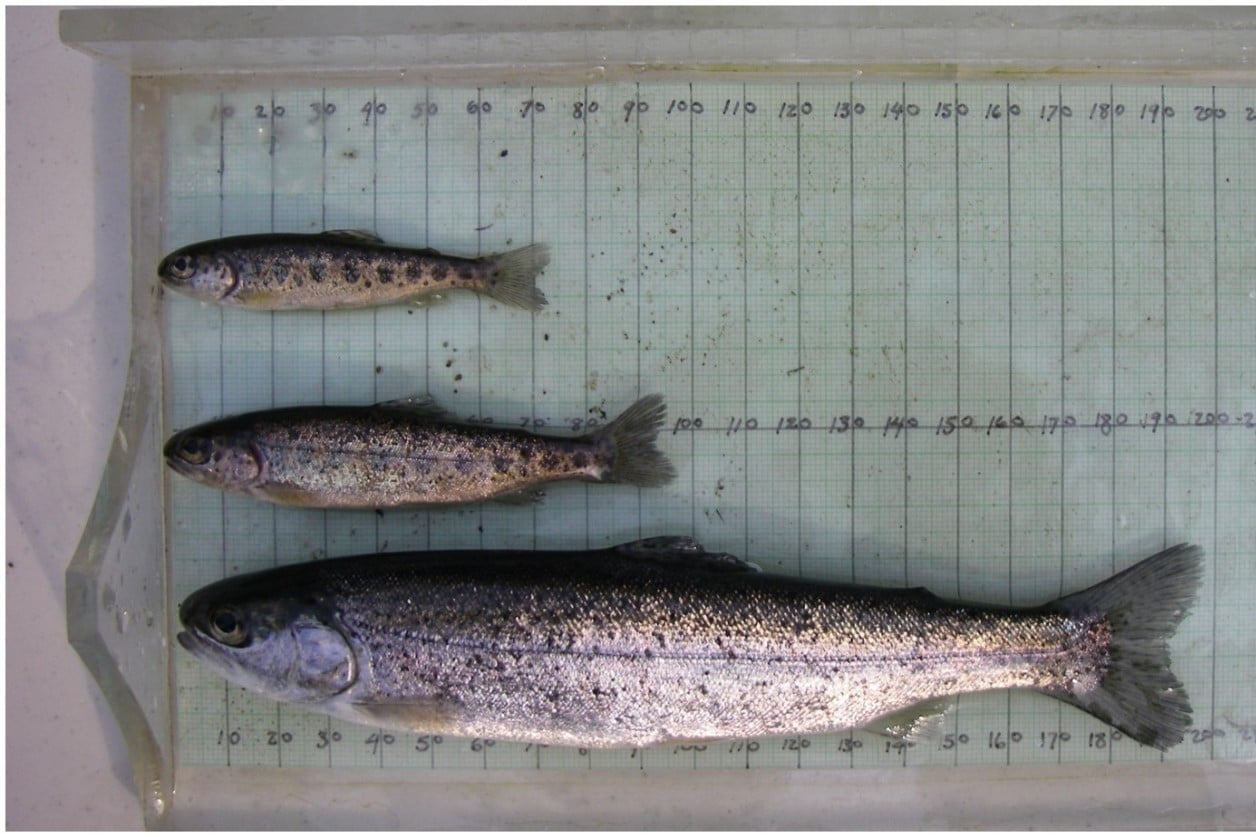

The study, published last week in the journal Ecosphere, revealed that the steelhead trout age of migration, as well as their size and numbers, is controlled by a combination of temperature, co-occurring salmon, and other factors. The trout may migrate to the ocean when they are only a year old and the size of a pinky finger, or when they are five years old and the size of a standard ruler.

In years following large returns of pink salmon, steelhead migrated to sea at a younger age, and in some time periods, there were more young steelhead that were produced from the river system.

In years following large returns of pink salmon, steelhead migrated to sea at a younger age, and in some time periods, there were more young steelhead that were produced from the river system.

“We think that energy-rich eggs from spawning pink salmon provide an important food source for young steelhead,” says SFU biology Ph.D. student Colin Bailey, who is leading the project.

SFU biology professor John Reynolds, a study co-author, also chairs the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC), the federally-appointed independent committee that assesses the status of species of plants and animals across Canada. He notes, “Many populations of steelhead are struggling, so the insights gained into their population dynamics can be helpful for conservation.”

Bailey adds, “It’s complicated — these fish seem to be controlled by many different factors at different times. We looked back through time and asked the data: do weather, spawning pink salmon, and other factors affect the steelhead life cycle?”

Bailey says the research results are made possible because of a remarkable long-term field program on the Keogh River on northern Vancouver Island.

Since the early 1970s, a collaboration between the Department of Fisheries and Oceans Canada, British Columbia Ministry of the Forests, Lands, Natural Resource Operations and Rural Development, and Instream Fisheries Research resulted in four decades of salmon and trout monitoring in the Keogh River.

Next steps include examining how the survival of steelhead in the ocean is influenced by their size and age at entry to sea. This will allow researchers to determine if there are lasting effects of steelhead rearing conditions on their chance of returning to spawn.

Source: Simon Fraser University