During the 21-day research cruise in September, scientists found eruption debris more than 25 kilometers (15 miles) away from the volcano, transported into the sea via the local river system and then dispersed by ocean currents. Their findings provide new insights into the fate of volcanic debris in marine environments and the strength of the current systems in Chile’s Northern Patagonian Sea. This, along with new seafloor maps, will help scientists understand volcanic hazards in Southern Chile and how they have changed over time.

After 9,000 years of dormancy, the Chaitén Volcano erupted without warning on May 2, 2008. Ash spewed 30 kilometers (18 miles) into the air and blanketed the landscape. Heavy rain in the following days triggered devastating volcanic mudflows known as lahars that cascaded down mountainsides and into the Northern Patagonian Sea. The town of Chaitén evacuated as the powerful mudflows inundated and transformed the landscape, flooding the city with mud and destroying the buildings on the southern side.

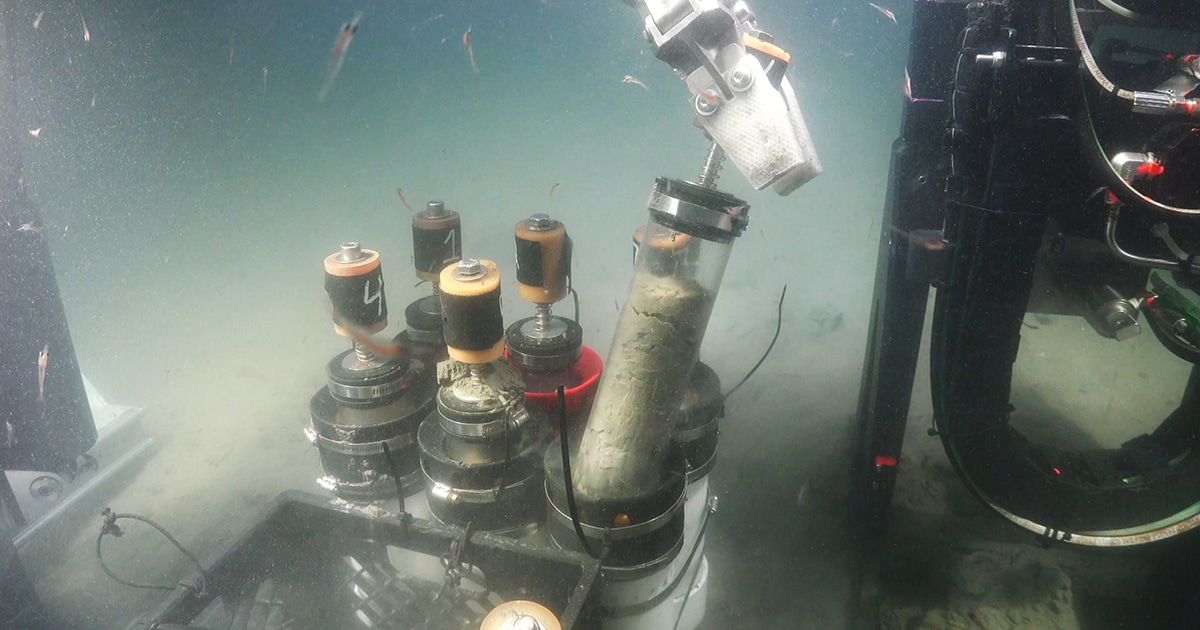

Using a vibrating coring device mounted on the Schmidt Ocean Institute’s ROV SuBastian, the scientists gathered seafloor sediment cores from the Northern Patagonia Sea offshore to the Peru-Chile Trench. Layers of mud within the cores provide a record of the region’s geologic and oceanic activity. Volcanic ash and debris indicate the occurrence of past eruptions in the area. These event layers are better preserved in ocean sediments than on land, shedding light on past events and providing the data needed to predict future volcanic hazards and assess how eruptions impact the marine environment.

“Our observations will allow us to explore how active volcanoes affect marine environments and infrastructure, ranging from fisheries to communication cables,” said the expedition’s Chief Scientist, Sebastian Watt, from the University of Birmingham in the United Kingdom. “A range of hazards can impact communities in the aftermath of volcanic eruptions, and the information we gather from studying the 2008 Chaitén eruption is relevant for coastal and island volcanoes globally.”

The international team included scientists from the United Kingdom, Chile, the United States, Italy, Malta, and New Zealand and was co-led by Dr. Rodrigo Fernandez of the Universidad de Chile, Dr. Rebecca Totten of the University of Alabama (United States), and Dr. Giulia Matilde Ferrante of the National Institute of Oceanography and Applied Geophysics (Italy). Throughout the expedition, scientists from three Chilean universities and the Chilean Geological Survey (SERNAGEOMIN) worked closely with the local Chaitén community to raise awareness of volcano science, geologic hazards, and the local marine environment.

“Communication with local communities and a broader global audience was just as important as the science activities of our expedition,” said Fernandez. “Months before the expedition, we introduced the project to the local schools. On our science team, we also included a teacher, Danny Leviñanco, who experienced the 2008 eruption from her nearby home of Chuit Island. With her help, we conducted lessons and ship tours with almost every child in this rural, remote region.”

The scientists mapped an area of the seafloor of approximately 2,700 square kilometers (1,042 square miles) in the fjords of the Northern Patagonian Sea and collected subseafloor data, imaging meters below the seafloor to assess the build-up and movement of sediment. The mapping revealed a stunning, glacially sculpted seafloor. Scientists have long known that the area was carved by glacial erosion but were surprised by the magnitude of observable ice scouring.

Other findings include undersea mega-dunes made from volcanic sediment outside a river delta transformed by the Chaitén eruption. The mega-dunes cover an area approximately three times the size of New York City’s Central Park. The scale of the dunes paired with high-resolution maps indicates a strong current system capable of moving large quantities of sediment.

“Approximately half of the earth’s volcanoes are islands or located near coasts, like Chaitén,” said Schmidt Ocean Institute’s Executive Director, Dr. Jyotika Virmani. “It is amazing that as recently as 2008, this volcanic eruption wasn’t predicted. Understanding volcanic activity and its footprint on the offshore ecosystem provides data to more readily predict the frequency and severity of events, which is essential to saving lives and cultures.”